This article is the third of my book review series. I'm trying to provide you with the best lessons from this reading. If you've missed the first two parts, please find them there :

This last and final part will highlight the deprecation policies used at Google. It will also talk a little about CI/CD and dependency management.

Depreciation and the Hyrum's Law

I talked about that law in the first part of this series. It negatively impacts the will of change as the more used a system is, the most likely it'll be hard to deprecate. Indeed, it can be hard to convince every stakeholder about the necessity of a change: it costs time, money, and the risk of regression always subsists. This is paradoxical because the more the system is used, the more critical the lack of change will be. For instance, every consumer may suffer the same security flaw simultaneously.

Book's authors suggest giving stakeholders metrics to convince them that change is better than the status quo.

Manage deprecations of obsolete systems

As their name suggests, obsolete systems often suffer from a lack of people with a deep knowledge of them. Knowing that your product depends on such systems can also be tedious. A typical example is transitive dependency: your application communicates with a recent API built by another team. But in the end, that API is just a facade of a more ancient, legacy system.

A standard solution to discover such dependencies is to shut down those obsolete systems and measure the pain caused by the interruption. This helps retrace the dependency graphs quickly.

The more frequent and the longer you practice those interruptions, the most likely your systems will be resilient and independent of the ones you want to deprecate.

The Googlers also propose to put some people in charge of handling the depreciation process. Establishing that responsibility helps avoid situations where the change would be delayed because of not a priority in the roadmap.

Dependency versioning

This is a common debate among developers: how should I version my dependencies? I agree with what's said in the book: we should ideally never ask ourselves what version to import. On a broader aspect: shared dependencies among different projects in the same organization should share the same version. This helps discover bugs, security flaws, and organize common changes in product teams.

In this sense, relying on the latest version available is a no-go. This likely leads to non-reproducible builds and unexpected issues.

SemVer limitations

Semantic versioning is a popular guideline for versioning artifacts. The version is made of three numbers. For instance, 2.2.1 stands for version major 2, minor 2, and corrective 1. By reading such information, an engineer should be able to expect a specific kind of change, and typically breaking ones.

However, that suit of numbers may not be reliable: major versions may be bumped despite no breaking changes being included. Corrective ones might not involve any fix but are automatically built at every commit by the CI/CD pipeline. Overall, sometimes SemVer overconstrains. Sometimes it does not enough. Actually, what's bein done with SemVer depends mainly on the maintainer's desiderata.

Some languages, such as Go and Clojure, handle them nicely: a new major is expected to be a brand-new package.

A side note on code review

No matter how well it's tightened to performant tools, code review is a matter of trust and communication. It has to be seen as a win-win process, where each participant learns from the other. Soft skills are essential. Confidence and empathy are required. Let's not forget that development is a creative activity. We often put a bit of soul into our code. As a reviewer, we must consider that when formulating corrections and improvements.

Static analysis tools

Static analysis tools like SonarQube are often considered when teams start industrializing their workflows. They provide a set of quite nice analytics (code smells, quality gates, etc.).

However, developers can reject them, mostly when false positives come up. They require manual investigation and therefore cost a lot of time. This is why the authors give three pieces of advice :

Focus first on the developer's happiness when introducing that kind of tool. Think carefully about the improvement and pressure it would bring.

Make the tools part of the development workflow. Code reviews often involve them as a first layer of analysis.

Make those platforms open for contribution. Encourage the contribution of the product teams, in adding new rules or tuning some in place.

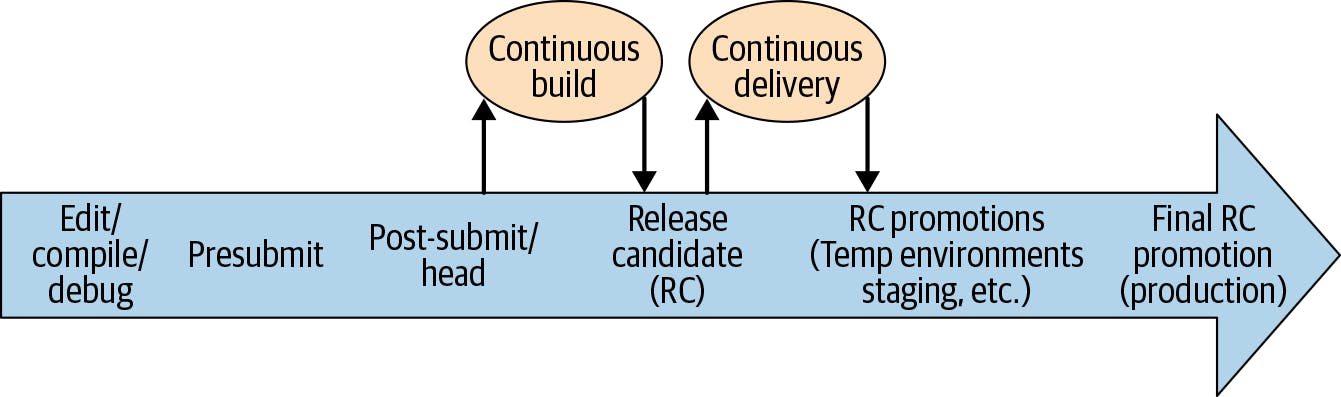

CI/CD

The first purpose of the CI/CD is to determine how safe the changes brought to the code are. Once this job is done, you'll likely look into deploying more frequently. Some patterns combine perfectly with your CI/CD pipelines.

The first one is canarying. This involves deploying a new feature to a small percentage of your end users (yes, in production). You do it to reduce the impact of a bad outcome compared to full deployment. Of course, it can be overwhelming to manage several versions in production.

The second one is feature flags. This consists in implementing mechanisms in your code to turn features off and on. They're typically piloted with remote configuration. Likewise, a canary release aims to achieve continuous deployment by lowering the risk and its impact.

The third one is A/B testing. This consists in testing two versions of your app at once. You implement metrics and decide, thanks to them, which one of A and B is the best version. You'll probably want to use A/B testing to compare two shopping funnels.

At Google, a classic build-to-run workflow looks like that:

Once the CI/CD has taken a great place in your development habit, you'll be tempted to forbid any release if its corresponding pipeline fails. The book authors warn about the risk of delaying an essential release because the CI/CD throws an alert. Sometimes, you'll need to go beyond it. For instance, to fix a critical security breach. As usual, I'd say that any kind of dogma is terrible. However, the development teams must be very confident in the impact of their developments if they decide to force a release.

Running the tests

You may lose confidence in the benefits of testing if they're flaky or if they delay your releases. That's why your tests must be as hermetic as possible. Ideally, they should be run against every change to track the issues fastly. The first option is to create a test environment. Second, even stricter, is to self-contain the test and fake its dependencies. It's a matter of balance here too.

At Google, they try to have Build Cops responsible for fixing the failing tests to make the build pass. They must drop their in-progress work to help the CI/CD flow restart.

Teams using git can also implement a pre-commit hook that forces the execution of the tests.

A note on open-sourcing your code

Open source is, to me, a great source of inspiration. Imagine giving such a significant amount of work to the community. For what in return? Almost nothing, and even sometimes the hatred of that community. We can think about the latest security flaw discovered in Log4j and the hate the maintainers received. Let's not forget that many giant companies use open-source projects daily without giving any form of support.

If you or your company decides to open-source, this can be seen at first as an excellent decision. However, beware of its negative impact on your reputation if improperly maintained or developed. The manner you deploy and synchronize your releases might also be more complicated.

An SRE mantra: No haunted graveyards

Google SREs formulated a mantra: there must be no haunted graveyards :

A haunted graveyard in this sense is a system that is so ancient, obtuse, or complex that no one dares enter it

This is a classic. Legacy code is overall hard to work with. This leads to a common strategy that I call the bandage strategy: every time your code is injured, you add a small bandage. But you never operate deep inside your product. In the end, too many bandages made the system unmaintainable: a total rewrite looks easier.

Besides the insane cost that implies such a decision, the system could freeze or go crazy without anyone having the skills to intervene.

As I've already highlighted, small and frequent changes help mitigate the risk. It's easier to propagate knowledge. They're easier to roll out and roll back too. Finding bugs becomes simpler.

Automation to help manage ego

When you advocate for a change, the impacted code may hurt its author's ego. Automation reduces that consequence. That's the role of this job. It doesn't imply any form of judgment.

Conclusion

This book review has come to an end. That was a very dense reading that I loved. I recommend you one hundred percent to take a glance at it. You have no excuse; it's free.